Dir: Lana Wachowski. Starring: Keanu Reeves, Carrie-Anne Moss, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, Jessica Henwick, Jonathan Groff, Neil Patrick Harris. 15, 148 minutes.

What other future could you imagine for The Matrix – the foremost reality-rupturing cultural phenomenon of the 20th century – than for its latest sequel to reveal that it’s all just been a fiction contained within its own protagonist’s head?

When we’re first re-introduced to Neo (Keanu Reeves), he’s back (somewhere) living under his old, fake identity of Thomas Anderson – now the widely acclaimed designer of a video game called the Matrix, which is, at almost every level, the same as the 1999 film we experienced in our reality. That realityalso includes the two sequels, Reloaded and Revolutions, which in this universe don’t seem to have been so unfairly maligned by the cultural consensus. He meets regularly with his therapist (Neil Patrick Harris), who helps him better define the lines between his reality and his fiction. But hold on – are those two things really separate at all? Somewhere, within that chaotic intersection of Neo’s life, art and memories, lies the truth that will finally set him free.

Already confused? Good. That means the Matrix is back, doing what it does best. It’s a volcanic cluster of ideas at a time when Hollywood is all-too content to slap the broad declaration of “it’s really about trauma!” on a film and call it a day. And that comes largely from the determined individualism of its director, Lana Wachowski (here taking solo reins of the franchise from her sister and usual co-director, Lilly) – whose outlook on The Matrix Resurrections both reasserts her personal vision and takes stock of the franchise’s thorny legacy. It’s also a reminder that long black coats and tiny sunglasses are, indeed, very cool.

Neo, at one point, is told that the powers-that-be “took your story and made it something trivial”. In Reeves’s pained response lies the mirror image of what the Wachowskis must surely have felt over the past two decades. Their greatest and most personal creation, rooted in their experiences as trans women, has become so diluted and divorced from its original meaning that the image of the red and blue pill is now co-opted by the alt-right as a way to publicly out themselves as conspiracy theorists and bigots.

Early on, Neo’s business partner (Jonathan Groff) reveals that their parent company, Warner Bros, has ordered a new Matrix sequel. If they don’t play along and agree to it, they’ll simply be bought out of their contract. It’s a sly reminder to audiences that this fourth Matrix instalment was, initially, developed without the involvement of the Wachowskis – cut to a writer’s room of bright-eyed millennials blithely tossing around ideas about what The Matrix is actually about, whether it be trans politics, crypto-fascism, or capitalist excess.

Whether or not it was created under duress, The Matrix Resurrections allows Lana her final say. Her script, co-written with novelists Aleksandar Hemon and David Mitchell (of Cloud Atlas fame), revisits the original trilogy’s ideas of self-liberation, rooted in Neo’s initial discovery that his entire world is but a computer simulation, a distraction from the reality that the human race has been turned into a living battery by the machines it failed to control. But it also uses those same themes to reach a new conclusion – that all binaries are bulls***, whether they be saviour versus saved, us versus them, or man versus machine. Even the choice between red and blue pill is something of an oversimplification.

The new cast – Groff, Harris, Jessica Henwick, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, Priyanka Chopra Jonas – all play a kaleidoscope of shifting identities. The film, admittedly, lacks a set piece quite as stark and revolutionary as the first use of “bullet time”, or the way Neo stopping bullets in mid-air for the first time really did feel like seeing the face of God. But it happily revisits and remixes all the familiar elements in ways that seem more attuned to the needs of characters than to the demands of spectacle.

Reeves? He still knows kung-fu. Henwick? She’s the natural action star here and defies gravity with steely grace. Abdul-Mateen? He dons a burnt-orange suit and discharges bullets from guns like they’re confetti streamers. Groff? He rips a sink off a wall with such ferocity that you’ll never be able to watch him in Hamilton the same way again.

Access unlimited streaming of movies and TV shows with Amazon Prime Video Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

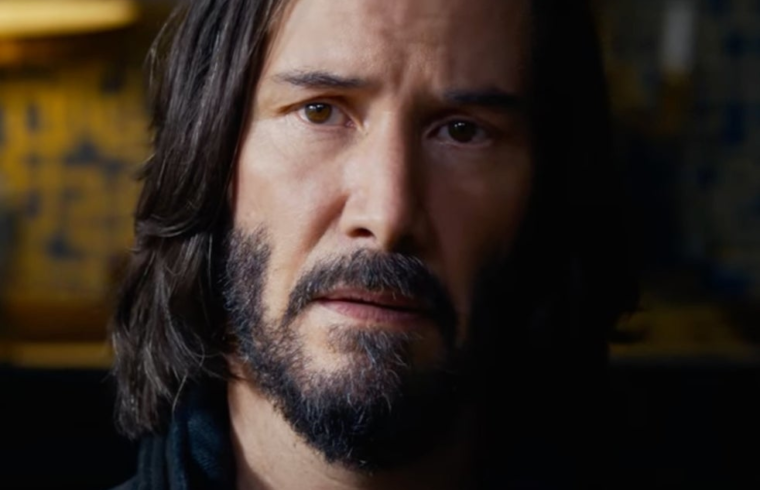

Keanu Reeves is back as Neo in ‘The Matrix Resurrections’

(Warner Bros Pictures)

But, for all the film’s souped-up shootouts, or its philosophising over minds and bodies, it’s love that ultimately emerges as the most transgressive force in the universe. When Neo drops by his local coffee establishment (called Simulatte, of course), we discover that he’s been harbouring a secret infatuation for one of its regulars, Tiffany (Carrie-Anne Moss), who bears a striking resemblance to the woman named Trinity in his game.

Reeves and Moss’s chemistry is as scorching-hot as it has always been – when they talk, the actors perfectly modulate their slightly too long-held glances and micro-smiles, so that these supposed strangers still act as if they’ve known each other since the dawn of time. The Matrix Resurrections ends with a literal call to the powers of sentimentality, empowerment and freedom – it ponders whether humanity finds any value in them which, in turn, seems to really ask whether audiences still have any interest in blockbusters of this purity and ambition. For my own stake, at least, I hope they do.